Pindus Mountains

The Pindus Mountains range runs along the border between Epirus and Thessaly, includes two national parks and some of the highest mountain peaks in the country.

The Pindus (or Pindos) Mountains is one of the mightiest mountain ranges in Greece, stretching from its northern borders west to the Ionian Sea, south to Metsovo, and east into Macedonia. The range runs along the border between Epirus and Thessaly, includes two national parks, the second-longest gorge in Greece, and some of the highest mountain peaks in the country.

Pindus Mountains National Parks

The Vikos-Aoös National Park was created in 1973 and covers the area around the Vikos Gorge, the second-longest in Greece after the Samaria Gorge and one of the longest in Europe. The larger Pindus National Park was created in 1966, in part to protect the Balkan and black pine trees that have covered these mountain slopes for thousands of years.

Here you also find Greece’s remaining wolves and bears as well as deer, wild boar, wildcats, and chamois. There are dice snakes and nose-horned vipers, too, so watch out if walking in remote areas. When not watching the ground for snakes, scan the skies for the birds of prey that survive here, including the goshawk, Egyptian vulture, golden eagle, imperial eagle, and griffon vulture.

These are rugged and potentially treacherous mountains, so consider hiring a guide if you really want to explore. The peaks are generally covered in snow from October until May, and when the snows melt the waters come cascading down the rivers. Paths that are easy to follow in midsummer can easily become dangerous.

Bears and Wolves in the Pindus Mountains

In these mountains of northern Greece some magnificent wild creatures survive, despite the Greek fondness for hunting and the farmers who kill anything that might threaten their often meagre livelihood. The most splendid – and rarest – of these wild animals are the European brown bear (Ursus arctos) and the European grey wolf (Canis lupus).

Sadly, you are unlikely to see either as they are considered at risk, but it is hoped that increased ecological awareness in Greece has come in time to save them. There are thought to be fewer than 200 bears and several hundred wolves, mostly concentrated in the national parks of northern Greece: Pindus, Prespa, and Vikos-Aoös.

Mount Smolikas

The ultimate challenge for serious trekkers in the Pindus mountains is Mount Smolikas, which is 8,459 feet (2,637 m) and is Greece’s second-highest peak after Mount Olympus. Reaching the summit will take several days, good preparation, and either your own camping gear or advance reservations for the mountain huts that provide shelter. Greece’s foot path network is not well-marked everywhere, and in some places the only direction signs are blobs of paint on the side of rocks.

The northern sectors of the mountains are remote and will satisfy anyone looking for a more rugged mountain experience. The accommodation may be simpler than elsewhere but the hospitality more than compensates.

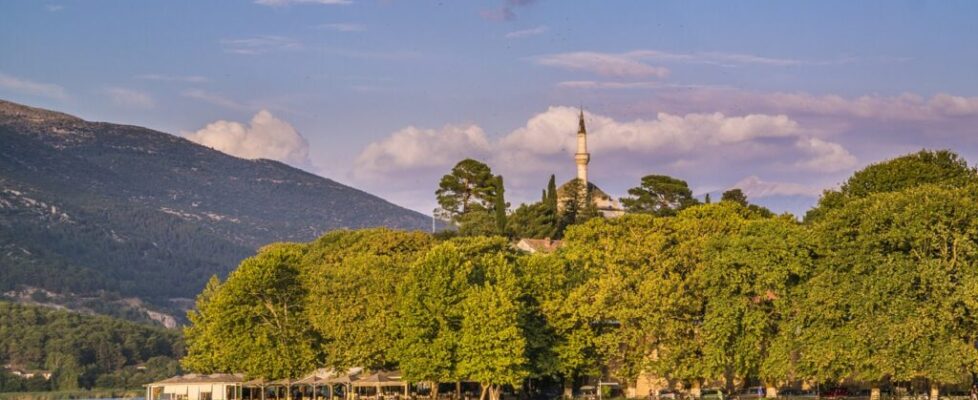

Konitsa

The small town of Konitsa, just a few miles from the Albanian border and an hour’s drive north from Ioannina, is a popular centre for walkers. There are a handful of hotels and eating places here, and a chance to hire local guides for exploring this remote corner. Konitsa has a beautiful setting, overlooked by Mount Trapezitsa and in turn overlooking the Aoös River, a river-kayaking destination.

Konitsa was badly damaged by an earthquake in 1996, and some of its older buildings were sadly destroyed. The old bazaar area survived, however, as did the small Turkish quarter, and both add some spice to this lively but remote town.

Mount Gamila

From Konitsa it’s possible to walk south to climb Mount Gamila (8,134 ft/2,497 m). This requires a night’s stay at the mountain hut at Astraka, and you can also take in a visit to the mountain lake of Drakolimni (Dragon’s Lake). Alternatively, heading east takes you to Mount Smolikas via the mountain hut of Naneh, and another mountain lake, also called Drakolimni.

The road running northwest from Konitsa goes towards Albania and after a 30-minute drive reaches the village of Molivdoskepastos, which is right by the border. It provides wonderful views into Albania and back towards the Pindus peaks of Smolikas and Gamila. Venture here and you have truly reached one of the more remote corners of Greece.